Introduction

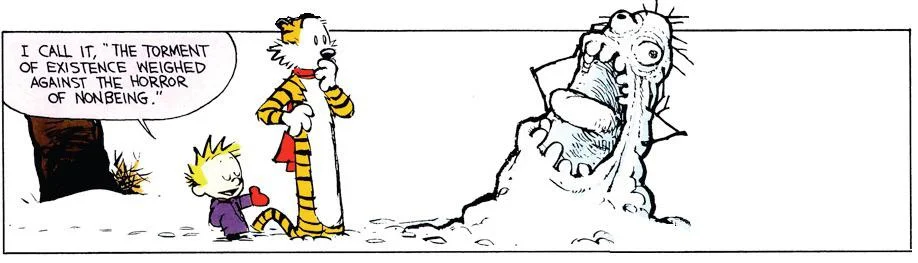

Existential horror is a subgenre of scary fiction that invokes the deep anxieties of meaninglessness, isolation, and absurdity in life. Unlike conventional horror, its terror often lies not in monsters or gore but in the realization that reality itself may be without purpose or order. Where traditional horror relies on exotic locations, moonlit graveyards, or abandoned houses, existential horror dispenses with these conventions. There is just life, without glamour or artifice. The dread comes from this uncanny familiarity—life itself turned inside-out.

Existential horror overlaps with the cosmic horror tradition of H. P. Lovecraft and others—both emphasize human insignificance—but it can also be psychological or everyday (as in Kafka or Beckett). Literary theorists note that cosmic horror explicitly instills psychological and existential terrors in characters and readers, making existentialism intricately connected to the genre. In short, existential horror confronts characters (and readers) with an abyss: the void of a purposeless world, oppressive freedom, and the breakdown of familiar meanings.

Philosophical Roots: Existentialism and Dread

The roots of existential horror lie in 19th- and 20th-century existential philosophy. Existential thinkers asked what it means to be free, alone, and aware of one’s own mortality in a world that may have no inherent meaning. Søren Kierkegaard, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Martin Heidegger all explored the anxiety and dread of existence.

Kierkegaard famously called dread the "dizziness of freedom": as people recognize they are utterly free to choose and are thus responsible for their lives, a profound anxiety sets in. Heidegger later described Angst as fear of "nothingness"—not an external danger but the void at the heart of Being. For Kierkegaard and Heidegger, dread has no specific object or cause; it is essentially anxiety in the face of existence itself. Fear, by contrast, is always directed at something concrete (a spider or a job interview); existential Angst is nameless, boundless, and universal.

Camus expanded these ideas in his notion of the Absurd. According to Camus, the human search for meaning collides with an indifferent universe. Life becomes absurd when we recognize the gulf between our quest for meaning and the world's silence. In The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), Camus famously declared that "there is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide"—arguing that facing absurdity head-on, rather than escaping it, is the fundamental challenge. Sartre likewise saw existence as brute fact, with each person "condemned to be free," forced to create their own values in a world without inherent meaning. For these thinkers, the horror is built into existence: we are born into a world without given essence, thrust into freedom, and left to make sense of it all.

Psychologists and logotherapists picked up on similar themes. Viktor Frankl, in Man's Search for Meaning (1946), talked about an "existential vacuum"—a feeling of emptiness and futility when people perceive life as meaningless. Rollo May and Irvin Yalom likewise describe existential anxiety as a basic human condition, arising from isolation, death-awareness, and freedom. In existential horror, characters often epitomize this vacuum: when their usual sources of meaning collapse, anguish and panic follow. In literature, this shows up as characters staring into the void of their existence—a terror that something is fundamentally wrong with the world itself.

Literary Antecedents in the Western Canon

The Western literary tradition offers many precursors to existential horror. In the 19th century, authors began foregrounding alienation, absurdity, and inner despair – themes that would shape horror in the 20th century.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864) presents a narrator who “has peeled back reality’s skin” and finds only meaninglessness and spite inside. The unnamed underground man’s torment at his own freedom and impotence anticipates existential horror’s theme of self-confrontation.

- Later authors made this explicit. Franz Kafka's unsettling tales like The Metamorphosis (1915) and The Trial (1925) plunge ordinary people into absurd, hostile worlds. Kafka's protagonist Gregor Samsa undergoes an existential crisis so extreme that his very identity dissolves, and the mundane world around him becomes grotesque and alien.

- Gothic writers also paved the way. Edgar Allan Poe’s stories (mid-1800s) explored inner torment and the thin line between sanity and madness. His tales of haunted rooms, decaying aristocracy or diseased minds often symbolize the emptiness lurking under civilisation’s surface. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) can be read as existential horror, too: the creature, alive without a soul or purpose, torments himself and his maker with the question of why existence was bestowed. More subtly, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) shows a woman slipping into psychosis under confinement; the horror is not a ghost but the crushing despair of having no control or outlet (a kind of existential suffocation).

By the mid-20th century, some works explicitly combined philosophy with horror. Jean-Paul Sartre's Nausea (1938) is a novel of existential dread rather than monsters, yet it reads like horror. Sartre's hero Roquentin experiences the world as if the material world threatens to invade and engulf him. Ordinary objects stir to a new and ghastly life of mindless, boundless abundance—chairs, trees, even his own body become alien and obscene. In short, Roquentin's nausea is horror without a monster.

Horror Fiction and Existential Themes

As horror became a distinct genre, writers began explicitly weaving existential themes into their works. One major influence is cosmic horror, pioneered by H. P. Lovecraft in the 1920s–30s. Lovecraft's stories feature ancient, indifferent forces and bizarre geometries beyond human comprehension. The terror is often described as existential: characters confronting Lovecraftian entities feel their minds shatter at the "cosmic terror" of reality's vast indifference. Although Lovecraft himself was not formally an existentialist, his vision echoes existentialist concepts—fatalism, absurdity, and the meaninglessness of human endeavor in an uncaring cosmos. Critics have noted that Lovecraft's "nihilistic cosmicism" shares philosophical DNA with Dostoevsky's underground man and Camus's absurd hero.

Meanwhile, traditional horror writers also explored meaninglessness. Stephen King’s The Mist (1980) is often read existentially: a supernatural fog traps townspeople and exposes their fears and beliefs. In the novel and film, a character’s breakdown and suicidal despair under unknowing threat highlight the horror of facing an uncaring unknown. King’s monsters and stories (like Pet Sematary) frequently challenge the idea of a benevolent universe. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959) has psychological horror and references to quantum mysteries: the house is described in mathematical terms (“standing so that the wind rises”), hinting that reality itself might be fracturing.

In academic terms, what makes horror "existential" is a focus on ontological crisis—the breakdown of ordinary experience into a confrontation with pure being. Scholars argue that existential horror involves the collapse of symbolic orders: horror becomes ontological because it exposes humanity to the "naked fact of being." In other words, when our comfortable categories (alive/dead, normal/monster, good/evil) fail, we face the unsettling presence of existence stripped of meaning. Cosmic horror does this with alien gods and non-Euclidean space; existentialist fiction does it with mundane reality turned uncanny. In both cases, characters (and readers) experience a crisis of meaning.

Key Ingredients of Existential Horror

Here are the recurring elements found in many works of existential horror:

- Alienation and Isolation: Characters feel profoundly alone or estranged (e.g., Kafka, Dostoevsky).

- Absurdity: Life’s events seem random or without reason (e.g., Camus’ The Stranger).

- Loss of Control: Society’s rules and science cannot explain the terror (e.g., Lovecraft, cosmic horror).

- Search for Meaning: Protagonists are forced to question the point of their lives (e.g., Sartre’s Nausea, King’s works).

- Moral or Ethical Vacuum: Conventions of right and wrong break down, revealing "evil" as mere indifference or meaninglessness.

These themes produce the distinct emotional tone of existential horror: it is a mixture of awe, dread, and often nihilistic despair. As philosopher Noël Carroll (1990) argues, horror often combines fear and disgust when something defies categorization. In existential horror, the “monster” may be abstract (nothingness itself) or mundane (an ordinary person realising his own insignificance), but the disgust and fear come from confronting a truth that we cannot easily digest.

Notable Examples in Fiction

Existential horror appears across classic and contemporary literature. Some landmark works include:

- Notes from Underground (Dostoevsky, 1864) – A proto-existential novella on meaninglessness and self-torment.

- The Metamorphosis (Kafka, 1915); The Trial (Kafka, 1925) – Surreal nightmare scenarios symbolising alienation and absurd justice.

- Nausea (Sartre, 1938); No Exit (Sartre, 1944) – Explicit existential novels/plays where characters face the void of existence.

- The Stranger (Camus, 1942) – Explores the absurdity of life and the courage of creating meaning.

- The Call of Cthulhu (Lovecraft, 1928) – Cosmic horror of indifferent gods and incomprehensible truths.

- The Fall of the House of Usher (Poe, 1839); The Tell-Tale Heart (Poe, 1843) – Psychological horror of madness and existential dread.

- The Stand (King, 1978); Pet Sematary (King, 1983); The Mist (King, 1980) – Modern horror often tinged with nihilism and cosmic indifference.

- House of Leaves (Danielewski, 2000) – A post-modern horror novel that breaks narrative form, highlighting subjective reality and existential dread.

- Never Let Me Go (Ishiguro, 2005) – A dystopian novel described as “existential horror” for its quiet yet devastating portrayal of fate and humanity’s deceptions.

Each of these works, in its way, forces characters to confront a collapse of normal reality or meaning. For example, in Kafka's Metamorphosis, Gregor Samsa's identity literally unravels as he transforms into vermin, his humanity dissolving until even his family cannot recognize him. In Camus's The Stranger, the protagonist's emotional detachment and the world's indifference leave readers with an unnerving void. Modern writers continue the tradition: Jeff VanderMeer's Annihilation (2014) makes the laws of biology alien; Liz Jensen's The Rapture (1996) and Michel Houellebecq's novels probe ecological and metaphysical despair.

Why do readers find this appealing? Interestingly, horror theorists note a "paradox of horror": we seek out these negative feelings voluntarily. Some scholars suggest that bridging existentialism and horror may explain this: readers vicariously face the fear of existence in a controlled way, sometimes finding catharsis or even meaning in the confrontation. Confronting the fear of nothingness in fiction can momentarily tame it, or at least make it a shared human experience. In any case, existential horror's popularity among writers and readers shows that dread of meaninglessness is a powerful form of terror.

Staring into the Abyss

Existential horror is not just about monsters or jump scares; it's about the terror of being human. Its roots lie in philosophical existentialism, where thinkers like Kierkegaard, Sartre, and Camus dissected the dread of freedom, death, and absurdity. These ideas permeated literature from Poe and Dostoevsky through Kafka and beyond, giving rise to stories where the real horror is reality itself. Such fiction often leaves protagonists and audiences exposed to the naked fact of being—a chilling reminder that in a universe without preordained meaning, our own existence can feel like a void filled only by our fears.

In the end, existential horror provokes the question: What if there is no ultimate meaning or comfort behind the curtain of reality? The answer it offers is dread – the slow, relentless anxiety of staring into nothingness – and the uneasy relief that confronting it might offer. That tension between dread and illumination is the literary legacy of existential horror, inviting readers to ponder the profound mystery (and terror) of our own existence.

References

Camus, A. (1942). The myth of Sisyphus. Éditions Gallimard.

Camus, A. (1942). The stranger. Éditions Gallimard.

Carroll, N. (1990). The philosophy of horror: Or, paradoxes of the heart. Routledge.

Frankl, V. (1946). Man's search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Hanscomb, S. (2010). Existentialism and art-horror. Sartre Studies International, 16(1), 1–23.

Heidegger, M. (1927/1962). Being and time. (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row.

Kierkegaard, S. (1844/1980). The concept of anxiety. (R. Thomte, Trans.). Princeton University Press.